October 27, 2016. By Mark Barry:

Our Global Spotlight series takes a dive into foreign economies and their big-picture impacts. This edition will include commentary and analysis covering the economic state of China, and will be posted in three issues: 1.The Great Rebalance (10/25/16) 2.Economic Transition and Reform (10/27/16) and 3.Risk of the Consumer (11/1/16).

Economic Transition and Reform

As mentioned in the previous segment of this Global Spotlight, for many years China followed an export-oriented economic model, relying heavily on manufacturing and fixed asset investment (investment in infrastructure, property, plant & machinery) for growth. Now, rising wages are causing China to lose some of its manufacturing competitiveness, with some manufacturers opting to move production to countries with lower labor costs such as Vietnam or Pakistan.[1] As a result, China must shift its economy sufficiently towards higher value-add manufacturing and services, or else it is likely to experience the “middle income trap” where growth stalls. This is well understood by Chinese policymakers, and the country has indeed started to transition from investment-led growth towards a more consumption-oriented economy with a focus on advanced manufacturing and services. This is reflected in GDP statistics, with the growth of China’s “old economy” slowing significantly while its “new economy” expands, albeit at a gradual pace.

While the “Great Rebalance” within China’s economy has begun, and the necessity of which is generally agreed upon by Chinese policymakers, outside economists, and other China watchers, there are still many challenges to its success. Overcapacity in the steel, coal, and other heavy industries needs to be reduced, a task that would involve shuttering or seriously reforming many of China’s SOE’s (state-owned enterprises) operating in these sectors. However, the government is limited by the fact that the resulting job losses would create political instability, as even minor reform has seen protests break out in China’s “rust belt” industrial north. The Party will not jeopardize its primary goal of maintaining control over the country, which limits the pace of reform. The debt burden of the nonfinancial private sector (again, mostly SOEs) is also a cause for concern, having grown rapidly post-2008 crisis. While there is debate over whether this debt buildup will lead to a destabilizing crisis, a significant portion of this debt is viewed to be implicitly guaranteed by the government, as a wave of failures would threaten political stability. Nonetheless, history tells us that a buildup in debt of this magnitude, if not preceding a financial crisis, typically leads to a prolonged period of slow economic growth.

Capital account reform and exchange rate liberalization are two other steps necessary in China’s transition to a consumption driven, developed economy. Higher consumption will erode China’s current account surplus and thus foreign capital will be required in order to finance it. Loosening capital controls would result in greater access for foreign investors, deepening financial markets and allowing for more sustainable growth. Exchange rate liberalization plays a key part in this by increasing convertibility of China’s currency, the Renminbi (RMB) and making it more likely that foreign investors are willing to hold it. All this would increase the role of the RMB in the global economy, something desired by China not only for economic reasons but geopolitical as well; the ascendance of the RMB as a global reserve currency would affirm China’s importance and influence in the global economy. This desire was seen in China’s push for the RMB to be included in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of major global reserve currencies, which recently succeeded. However, this move is more symbolic than anything else, as global reserve currencies are ones that foreign central banks are willing to hold in size, which is unlikely to be the RMB anytime soon given its convertibility issues.

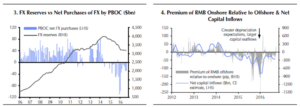

While some progress has been made with respect to opening up the capital account and liberalizing the exchange rate, recent events have likely caused future reform to be put on hold indefinitely. Over the past year, many market participants have become concerned that China’s slowing economy coupled with a Federal Reserve tightening cycle would lead to the RMB depreciating against the dollar, accelerating capital outflows. A sharp depreciation would also reduce consumer purchasing power, which would drag on the economy’s transformation to a more consumer oriented economy. While the onshore RMB is not freely convertible and is only allowed to trade in a tight band around a fixed rate set by the authorities, there are no such restrictions on the offshore RMB traded in Hong Kong, which has traded at a discount to the fixed rate of its onshore peer. The PBOC has intervened heavily in the offshore Yuan market in order to minimize volatility around its fixed rate and maintain confidence in the RMB, which has used up a considerable amount of its Fx reserves.

Source: Capital Economics, Thomson Datastream, Bloomberg, CEIC

However, while the PBOC has and likely will continue to intervene in order to maintain a relatively stable exchange rate, it has over the past year allowed the RMB to depreciate against the dollar, albeit in a slow and steady manner. Investors rightly fear an unorderly RMB depreciation, which would roil financial markets, but should this managed depreciation continue, both China and the rest of the global economy should be able to cope.

These are just a few of many reforms necessary for the success of China’s Great Rebalance, with numerous books devoted to the topic. The transformation of the Chinese economy is a huge task, and the path it takes along this transformation will impact both global economic growth and financial markets. Ultimately, China must strike the right balance, not rebalancing too quickly which would result in a hard landing, nor delaying reforms that if not undertaken would stunt future growth. Understanding that China faces a difficult path moving forward, we will take a look at some positive developments within the economy and opportunities for investors in our next and final segment of this series, ‘Rise of the Consumer’.

[1] Magnier, Mark. “How China is Changing Its Manufacturing Strategy.” The Wall Street Journal. 7 June 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/how-china-is-changing-its-manufacturing-strategy-1465351382