Measuring Inflation: CPI vs. the PCE Price Index

June 23, 2022. By Matthew Okaty:

Understanding all the inflation data presented in the news can be confusing at times, especially since there are different ways of measuring inflation, and it is not always clear which form of measurement (or index) is being used. Take this headline from CNBC earlier this month: “Inflation rose 8.6% in May, highest since 1981.” Since the Fed considers a certain level of inflation, essentially 2%, to be generally healthy for the economy, one might think based on this headline that inflation is currently more than four times higher than the Fed’s targeted goal. But that would not be an accurate statement because the index used for the headline is not the same one used by the Fed. Granted, the article goes on to explain which index it was citing (the Consumer Price Index), but we don’t always have time to read the full article, and we get so many numbers thrown at us these days that unless we know and understand the frame of reference, we run the risk of comparing apples to pears.

The two main indexes used for tracking inflation are the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE Price Index). More people tend to be familiar with the CPI, perhaps because it’s more often cited in the news. A version of this index is also used by the Social Security Administration for calculating cost of living adjustments for benefits. However, the PCE Price Index is the one used by the Fed for gauging inflation and determining monetary policy (such as raising interest rates) and therefore just as important to know about. So how do the two indexes differ?

To begin with, the CPI is produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and sourced mainly from voluntary surveys sent to urban consumers (rural consumers are not sampled). The PCE Price Index, on the other hand, is produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and sourced mainly from mandatory surveys sent to businesses. This difference in how the information is sourced can plausibly affect the results in a number of ways. Due to the nature of voluntary surveys, the people who choose to respond may not necessarily be representative of the population as a whole and may also underreport certain items (such as alcohol and tobacco). Additionally, individual consumers are perhaps more prone to mistakes when trying to estimate or recall certain expenditures versus businesses that are required to keep records. But the data coming directly from businesses in the PCE Price Index can have certain limitations as well. For example, the indexes are supposed to track consumer spending, but PCE data can not always differentiate between personal and business expenditures (Best Buy has no way of knowing if a particular computer was purchased for personal or business use).

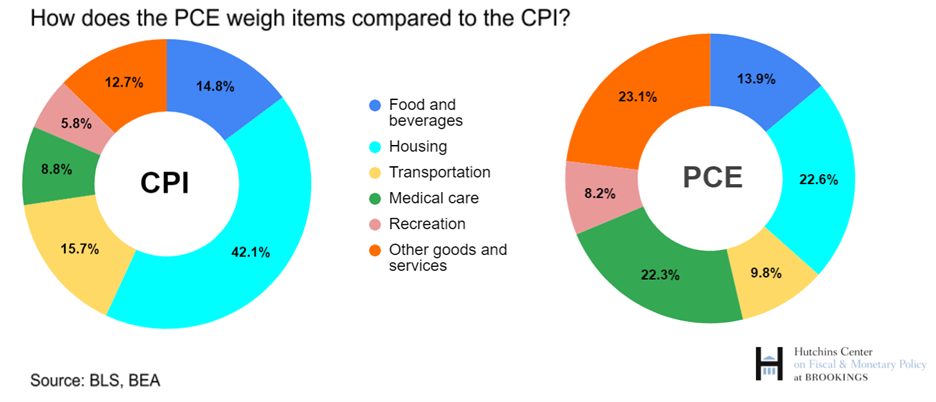

Another major difference is that the CPI only includes expenses directly incurred by consumers (i.e., out-of-pocket expenses), while the PCE Price Index also includes expenses paid by third parties on behalf of or for the benefit of consumers, such as employer-provided health insurance. Thus, the PCE Price Index is larger in scope, and this also has a dramatic effect on the weightings given to the component categories. As you can see from the chart below, medical care spending represents approximately 9% in the CPI but a whopping 22% in the PCE Price Index. A change in the cost of medical care will thus have a much more significant impact in the PCE Price Index versus the CPI. Conversely, housing costs represent almost twice as much in the CPI (42%) as it does in the PCE Price Index (22.6%), and thus the CPI is more sensitive to changes in housing related expenditures.

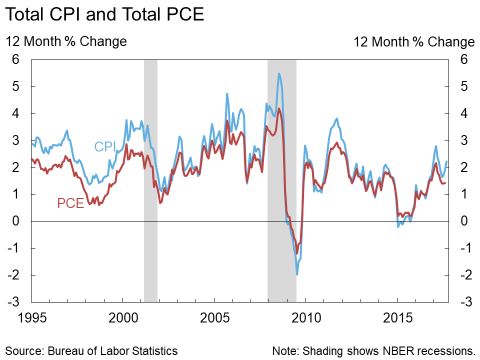

The last major difference is that, unlike the CPI, the PCE Price Index takes into consideration the fact that consumers will often substitute goods (i.e., change what they buy) in response to rising prices. For instance, if the price of beef goes up, people may start buying more chicken instead. Thus, even if prices for certain preferred items go up, overall consumer spending could theoretically remain unchanged depending on consumer behavior and the willingness to substitute goods. The CPI does not account for this, though, because the basket of goods and the corresponding weightings it uses in its consumer surveys is fixed and only changed every 2 years. As a result, the CPI can tend to overstate cost of living increases and generally tracks higher than the PCE Price Index as can be seen in the chart below. Because of this, Congress actually passed a law in 2017 that changed the index the IRS uses when adjusting tax brackets each year from the CPI to a different version of the CPI called the “chained” CPI which reflects changes in consumer buying patterns.

While the Fed’s 2% long-term average inflation target is based on the PCE Price Index, in the short-term they generally focus on what is referred to as the “core” PCE Price Index which excludes the categories of food and energy. This is because food and energy are traded commodities that are susceptible to a range of forces largely outside of the Fed’s influence (such as wars, droughts, and supply change disruptions) and tend to experience more volatile price swings. Including those categories can skew the inflation numbers and might not necessarily be indicative of the overall state of the economy. Differences can be considerable. Using the latest figures from April 2022, the total PCE Price index rose 6.6% from a year prior, whereas the core PCE Price Index (which excludes food and energy) rose only 4.9%. The difference is even more considerable when compared to the CPI which rose 8.3% for the same time period.

While arguments can definitely be made as to why one index is better than the other, it’s really a matter of perspective and depends on what you are measuring. The CPI is arguably better at determining the level of inflation individual consumers are actually experiencing because of its narrower out-of-pocket scope. But when measuring inflation in the economy as a whole, the PCE Price Index is probably more useful as it contains spending on consumer goods whomever the buyer is, including institutions. There are other differences and additional indexes out there as well, but hopefully this helps clarify some of the major inflation data being presented in the news.